My presentation this summer at the ANA/BMA conference – the largest B2B conference in the world – crystallized my experiences from a year-and-a-half of consulting with big businesses that want to compete more effectively with disruptive startups.

Why? Because if you are part of a large enterprise, that is what you MUST do to stay relevant and competitive.

I also challenged my audience made up mostly of marketers to redefine “marketing.” Here’s a brief excerpt from my talk:

That’s because every C-suite executive I’ve spoken to readily acknowledges that they look to marketing officers for insight and knowledge about customer needs and experiences. These customer insights are essential to set the strategy of the company.

The reason CEOs look to marketing is that only marketing is specifically tasked with looking out for customers. Even though that’s something everyone in the company should do.

To fully fulfill this expanded role as strategic business leaders and navigators in this new era, we need to define, explore, confront and resolve what I’ve come to call The Three Paradoxes of Innovation. For those of you in firms of any meaningful scale, these are particularly relevant for you!

Let’s take them one at a time.

Painful Paradoxes of Innovation #1

Innovation is disruptive so how do you change everything … while you keep calm? How do you embrace disruption while you keep calm?

We do it by getting comfortable with being uncomfortable.

As you can imagine, that’s a lot easier said than done.

But here’s what I learned working with the innovation leaders of big companies – in large part because I’ve been there myself – the first step to reduce the terror and anxiety that grip even the most foresighted leaders of incumbent players is to help them understand where all these darned startups are coming from.

Which is nowhere and everywhere – and, in particular, out of left field.

What today’s marketers and business leaders need to understand – deeply – is that startups come out of nowhere and everywhere for certain reasons. Startups are the true and in many cases the only beneficiaries of three transformative trends:

- Rapidly decreasing costs

- The accelerating pace of specialized knowledge

- Every device and machine becoming digitized and connected.

Let’s take a quick look at all three trends.

- Rapidly decreasing costs.

A few years ago, buying a drone would have set you back tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars. Today, you can pick one up for a few hundred bucks at Best Buy.

The same goes for 3D printers and DNA sequencing. The upshot is that tiny startups armed with next to no financial capital but boatloads of cheap intellectual and human capital can come out of nowhere, most often from outside your industry.

These tiny startups take on the big guys and in some cases eat them for lunch because the financial barriers-to-entry are so low. In some cases, they’re nonexistent.

Uber owns no cars, but it disrupted an industry and made itself more valuable than many car manufacturers.

Uber, Airbnb, Netflix, Kickstarter, Waze and GitHub (to name just a few) sprang into being and went on to very quickly devour not just companies but whole industries. Even though they’re armed with next to no physical assets and only a handful of employees.

Uber owns no cars. Airbnb owns no hotel rooms. Facebook is the largest media company in the world but employs no reporters, videographers or editors. Amazon become the largest retailer in the world before it ever opened a physical store.

Paradoxically, what these companies don’t have is even more important than what they do have. And what they don’t have is:

- Baggage, physical or metaphysical.

- Fixed ways of doing things, or the idea of “not invented here.”

- Traditional organizational structures complete with built-in costs, complex bureaucracies, hierarchies and legacy systems.

What they do have is ideas.

In today’s world, ideas are often more than enough to get started. Ideas can be more than enough to win.

- The accelerating pace of specialized knowledge

Ideas don’t need specialized knowledge to be conceived of or to take off. It didn’t take a technology genius to invent Facebook.

The service that Facebook delivers wasn’t something anyone could have imagined they wanted, much less would they have been willing to pay for it. It most likely wouldn’t have occurred to an engineer, at least not to someone who thinks like one, in his or her wildest dreams.

Mark Zuckerberg and pals didn’t need the Silicon Valley garage that Dave Packard and Bill Hewlett used to start Hewlett-Packard. Like Dell Computer founder Michael Dell, all they needed was a college dorm room to get the ball rolling.

In both cases, the new ideas that created multiple billions in economic value weren’t technological advances, but business model advances.

The Apple App Store and the Google Play Store didn’t exist before the summer of 2008. But today, between them, they create untold billions of enterprise and economic value.

- Every device and machine in the world already is or is being digitized.

We’re just entering the early days of the Internet of Things. Projections are that there will be 20 billion connected devices operating in the world by 2020. And 80% of them will be devices and machines connected not to people, but to other devices and machines.

As it turns out, the Internet of Things (IoT) is something of a misnomer because the winning ideas are all essentially services:

- Alphabet’s Nest sells an automated remote control that lets you manage all the things in your house when you’re not there.

- Uber isn’t selling a “thing” but a set of wireless connections that provide transportation services.

That means something simple: software rules hardware. Which means a painful (for incumbents) and exciting (to new entrants) reality is born, which brings us straight to Paradox of Innovation #2.

Painful Paradoxes of Innovation # 2

We need to think horizontally but act vertically.

Let’s start to resolve this one by posing a basic question first: What is innovation?

One simple answer is that it is very different from what it was in the past. For centuries, innovation was all about inventing new and better things: a new and better mousetrap, a new and better means of transportation from the wheel to the automobile, a new and better jet engine.

But today, the lion’s share of disruptive and value-creating innovation is about creating and evolving new business models.

I call this market-led, as opposed to technology-led, innovation.

I don’t mean to diminish the impact of technology because its ultimate impact is vast, perhaps immeasurable. But the fact is that, over the past decade, 2% of innovations have produced 90% of the new value. That trend is expected to continue and it’s clearly accelerating today.

So the most radical and threatening disrupters are likely to come from beyond the boundaries of your industry’s vertical market.

We need to think horizontally about the nature and source of future threats. That’s because they’re not exactly going to come out of nowhere, but rather out of somewhere you need watch closely before they emerge.

Now, another aspect of horizontal innovation involves the use of data. Everyone has heard about big data, predictive analytics and the like and the enormous impact data applications have on our ability to innovate.

Well, data is flowing across all industries in ways that we never imagined. The compounding effect of Moore’s law is having an astronomical effect on data’s disruptive nature in industry after industry after industry.

So how might this affect your industry, one might ask?

Here’s how. Many of the most disruptive startups have come completely from outsidetraditional industry verticals:

- You need not think much past Uber to recognize that no one in the transportation industry came up with it.

- Likewise, Airbnb is a hospitality competitor but not one incumbent in the hospitality industry tried it!

- Oh, by the way, Tesla and electric cars are the same.

- So are Netflix and movies.

You get the point. The horizontal disruptor, or disruption coming from outside existing industries, is very real. It surely affects many of what we think of as traditional vertical industries.

Painful Paradoxes of Innovation #3:

Think and play big, but act like a startup.

If you’re in a big company, I’d advise you tothink small, as in “more like a startup.” If you’re in a small company or startup, you’re going to need to think big if you want to grow large and fast enough to achieve scale.

One of the more ironic paradoxes that I’ve come up in my business is this. I have yet to meet a startup that doesn’t want to get big. Yet very big enterprises want to act small. What gives?

Think about it. Entrepreneurs want to change the world they want to solve problems. Heck, in the end, they even want to cash out and sell to a corporate giant.

If you go read the startup material, it’s all about thinking big and acting big. Of course.

I ask you again: “What entrepreneur wants to say small?”

So, isn’t it ironic that every big company is going crazy trying to figure out how to act like a small startup? We all want to act like “entrepreneurs.”

I think this paradox is the most perplexing of all. Big companies have all the resources that a small company desires: scale, customers, capital and smarts. The list goes on and on.

So, if you’re a large enterprise, you’ve got to come up with some ways to marry acting big with acting small. Sound easy?

Well, not exactly, but there is good news. There are emerging learnings out there right now on exactly how to get started.

That’s what we did at GE five years ago, when we launched Fastworks.

In 2014, at GE we engaged nearly 5,000 team members who came up with some 7,500 new product concepts.

That feat was impressive in its own right, but even more so when you stopped to think that not one of our product developers worked for GE!

What we did was to crowd-source. We took tools and techniques developed by the consumer gaming industry and applied them to developing hardware for our industrial companies.

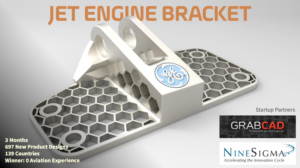

Crowdsourcing the design of a GE jet engine bracket elicited ideas from entrants in nearly 140 countries. The winner’s aviation experience? Zero.

We partnered with startups on a crowd-sourcing program. We put out the specs for a mission-critical part in a GE jet engine. Our mission was to radically rethink and design a structural steel bracket to dramatically reduce its weight while increasing its strength and resilience.

We had about 2,000 world-class structural engineers working full-time at GE when I told the head of that division that we were preparing to conduct “a simple test” on the marketing side.

We were going to crowd-source the development of a mission-critical steel bracket that helps to hold up a jet engine by partnering with a few startups and holding a contest.

As you can imagine, that conversation went well.

But despite what you might cordially call skepticism from within the ranks, we pushed ahead with a contest. We found entrants from nearly 140 countries to design this zero-tolerance jet engine bracket to our exacting specifications.

The winner was a young software engineer from Indonesia. When we announced his name, CEO Jeff Immelt asked me how many years of aviation design experience the guy had when he entered. My reply was simple: “Zero.”

When GE CEO Jeff Immelt asked me, “How many years of aviation experience did the winning innovator have?” I answered, “Zero.”

I left the BMA audience with a few questions to ponder back home:

- What digital ideas are out there that have the potential to disrupt your business or industry?

- Who in your industry is crowd-sourcing and crowd-sharing?

- Startups inside big companies aren’t real startups– so get over it, but at the same time, get started on it.

- What can do you do today to acquire the skills, insight and knowledge you need to start resolving these three paradoxes in your own field?

- How are we going to change the way that we work?

Here’s one final thought before you and I move on: Your clients and customers are fighting the same battles you are.

So who is helping your customers? I sincerely hope that you are.

Until next time, I’m Steve Liguori.